And given its similarities in DNA, the Chincoteague pony seems likely, too, to have some Spanish ancestry. “I was like, Wait, what are they exactly? What are these Chincoteague ponies?”īecause this tooth was buried at a well-documented site in a Spanish city that existed only from 1503 to 1578, archaeologists are pretty sure the Spanish brought this horse to Puerto Real. Delsol, who is French, had never heard of it. When he did finally return to the tooth, though, he saw that its DNA sequence was similar to that of a… the Chincoteague pony.

He put it aside for weeks to finish his cattle project. Delsol picked 24 to analyze DNA from and-just his luck-one tooth had sequences that looked really, really weird. He was interested in cattle domestication in the Americas, and the museum’s collections contained hundreds of cow teeth from Puerto Real, a 16th-century Spanish settlement in modern-day Haiti. Nicolas Delsol, now a postdoctoral researcher at the Florida Museum of Natural History, was not thinking about any of this while dealing with the troublesome “cow” tooth for his Ph.D. Given the genetic similarity, could the myth be real after all-were these mysterious ponies also Spanish colonial horses that first arrived by shipwreck? And intriguingly, a recent DNA analysis suggests that the modern breed this Spanish colonial horse is most closely related to is none other than the Chincoteague pony. The National Park Service, which manages the northern half, tells a decidedly less romantic tale: 17th-century settlers probably brought these horses with them.Įnter now the “cow” tooth, actually a horse tooth, mistakenly cataloged decades ago by archaeologists excavating an abandoned 16th-century Spanish settlement. Today, the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Company, which manages the southern half of this horse population for historical reasons, promulgates the shipwreck origin story of the island ponies. “The seasons came and went,” the book goes, “and the ponies adopted the New World as their own.” In their newfound freedom, they became wild-or technically, feral, domesticated but untamed. The crew perishes, but the ponies swim to a nearby island and survive. A Spanish galleon carrying Moorish ponies to the gold mines of Peru shipwrecks off the coast of what will later become Maryland and Virginia. No one knows how the horses first arrived there, but Misty of Chincoteague retells a dramatic bit of local lore. A band of wild horses still roams that island today, eating seagrass and largely ignoring tourists who come for selfies with a real-life version of Misty.

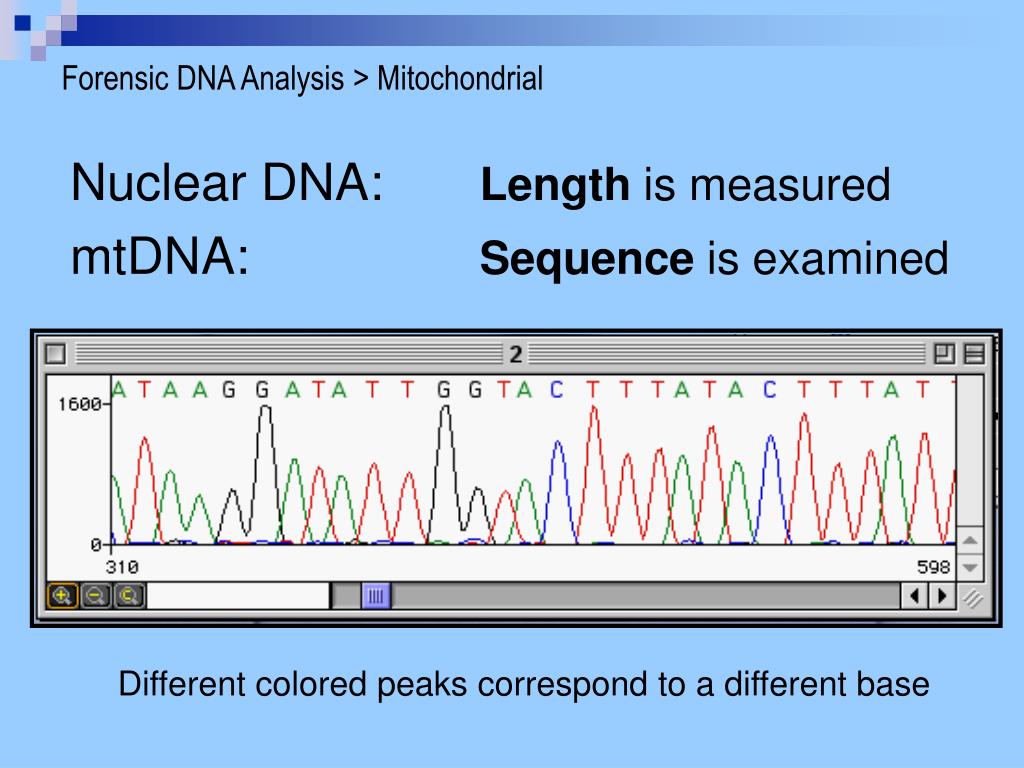

The story is fictional, but the setting is real. For everyone else: This beloved 1947 children’s novel tells the story of Misty the pony, born on the beaches of an uninhabited barrier island. If you know, you know-horse girls, I’m looking at you. We conclude that a mitochondrial genetic modifying factor is not present in congenital myotonic dystrophy.To tell the story of how a purported cow tooth dug up in the Caribbean might corroborate the mythical origin of wild horses off the coast of Maryland and Virginia, let us begin, naturally, with a children’s book, Misty of Chincoteague. Comparison of the two sequences with control data failed to reveal a specific nucleotide variant or length variant in this disease. To investigate this possibility, we sequenced completely the mitochondrial genome in 2 patients with congential myotonic dystrophy. The congenital variant of myotonic dystrophy, in which there is a striking maternal inheritance pattern, is a likely candidate disease. Mitochondrial genetic modifying factors have been suspected in several autosomally inherited diseases. Mitochondrial DNA sequence analysis in congenital myotonic dystrophy Mitochondrial DNA sequence analysis in congenital myotonic dystrophy

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)